Stepping Up

Even as he travels the world, dancer and hip-hopper Marc Bamuthi Joseph has stayed close to his musical roots

San Francisco's Intersection for the Arts was throbbing with the beats of deep soul and house music. In a corner, a boy was break dancing, gleefully spinning on his back, oblivious to passersby slowly gravitating toward the DJ booth in the gallery exhibit, a politically charged multimedia work about the history of cocoa and chocolate.

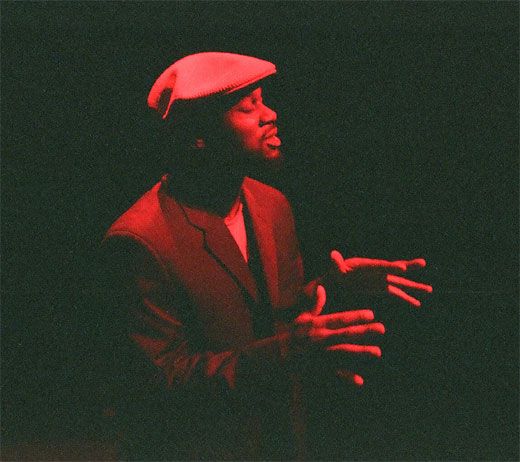

The youngster might have been Marc Bamuthi Joseph 25 years ago. In fact, he was Joseph's 5-year-old son, M'Kai. Joseph, curator and emcee for the program about to start, was nearby—feet sliding to the beat beneath his gracefully gyrating hips, arms waving weightlessly as hands fluttered in welcoming gestures. Like his son, Joseph seemed in perpetual motion that night, the launch of the 2007 Hybrid Project, a yearlong program of performances and workshops integrating dance, poetry, theater, and live and DJ'd music.

Joseph, 31, is the Hybrid Project's lead artist. He is also artistic director of the Bay Area's Youth Speaks organization, which encourages activism through the arts, and its Living Word Project theater company. Though he is perfectly at home in those positions, he is hardly ever at home. Performances, dance apprenticeships, teaching and artist residencies keep him hopping around the United States and as far afield as France, Senegal, Bosnia, Cuba and Japan. The New York City native has been on the move since childhood.

Like a character out of the movie Fame, Joseph seemed destined for stardom from the time, at age 10, he understudied Savion Glover in the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical The Tap Dance Kid, then assumed the lead in the national touring company. But in the early 1990s, after dabbling in television, Joseph embarked on a search for an artistic identity that had less to do with the box office and more to do with what he calls "shifting the culture"—away from the compartmentalization of the arts and toward their fuller integration into daily life. That journey was rooted in the hip-hop culture of rap, DJing, b-boying (break dancing) and graffiti that arose in the Bronx in the late 1970s and grew into a nationwide movement in the 1980s.

"I have non-hip-hop-related memories of being 3," Joseph says, laughing, "but it's the music that I started listening to at 6, 7 years old. It's pretty much always been the soundtrack for my life."

Joseph's trajectory toward theatrical hip-hop—he is an internationally acclaimed performer who pushes the African griot (storyteller) tradition into the future with music, dance and visuals—rose steeply after he earned his B.A. in English literature at Morehouse College, in Atlanta, in 1997. A teaching fellowship took him that same year to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he quickly found a calling in the world of spoken-word poetry.

Joseph's ambitious solo works integrating spoken word and dance won him the 1999 National Poetry Slam Championship (with Team San Francisco) and made him three-time San Francisco Poetry Grand Slam champion. His breakthrough "Word Becomes Flesh" (2003) took the form of spoken and danced letters from an unwed father to his unborn son; "Scourge" (2005) addressed issues of identity he faced as a U.S.-born son of Haitian parents. "the break/s" is a personal spin on Jeff Chang's Can't Stop Won't Stop, the American Book Award-winning history of hip-hop.

Joseph read Chang's book in 2005 while in Paris working with Africa-based choreographers. "I had the epiphany that hip-hop has really impelled me and enabled my travel throughout the world," he says. "Jeff's book articulates, better than anything I've ever encountered, the full breadth of why we are what we are, and how we got to this place."

Self-scrutiny is the jumping-off point for Joseph's work. "The autobiography is a point of access for audiences, but it's also a point of access for me," he says. "I think the vulnerability—but specifically the urgency—onstage makes for the most compelling art in this idiom. If there isn't something at stake personally in making the art, then why bother?"

Despite the rapidly rising arc of his stage career, Joseph remains committed to teaching, especially as a mentor to Youth Speaks and the Living Word Project. "Working with the young people always inspires me; it pushes my humanity, it forces me to find creative means of exciting the imagination," he says. "That's really where it begins. I think there's no better place in our culture than the high-school classroom to introduce new ways of thinking."

Derk Richardson is senior editor at Oakland Magazine and hosts a music show on KPFA-FM in Berkeley, California.